What do we know about Dobson’s paintings?

Just as our knowledge of William Dobson is limited to information that survived the Civil War, much knowledge about his paintings has also been lost. Only one painting actually bears the signature of the artist, An Unknown Woman in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. The majority of his paintings are confidently attributed to Dobson based on stylistic analysis, as well as considering the importance and whereabouts of his sitters during the Civil War.

But several Dobson paintings continue to frustrate art historians because the sitters cannot be identified. In the research for this celebration we have uncovered some of the missing identities.

If you have any information about William Dobson that you wish to share, please get in touch. See the Contact page for details.

William Dobson in Ashdown House

On the third landing at Ashdown House hangs a splendid group portrait of three prominent cavaliers. The artist is William Dobson, court painter to King Charles I, and the picture was painted in about 1644, during the English Civil War, when Charles’ court was based in Oxford. The names that are painted onto the picture are those of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, his brother Prince Maurice and the Duke of Richmond. This is the first mystery about the painting – the names of the sitters were added at a later date and two of them are incorrect. Whilst Prince Rupert is definitely the focal point of this painting, his comrades are Colonel Murray and Colonel Russell. A second mystery is why the painting is unfinished. The detail on Prince Rupert’s clothes has not been completed and there is no glass containing the red wine. We can speculate that perhaps the person who originally commissioned the painting never returned from the wars to pay for it.

It is entirely appropriate that this portrait should hang at Ashdown, a hunting lodge built circa 1662 for William, First Earl of Craven. Craven was a lifelong supporter of the Royalist cause and an ardent admirer of Prince Rupert’s mother, the beautiful and charismatic Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, the Winter Queen. It was Elizabeth who bequeathed to William Craven the splendid portrait collection that hangs in Ashdown House today. Craven and Rupert were friends and comrades in arms during the 30 Years War that ravaged Europe during the early years of the 17th century. Craven was also the executor or Rupert’s will and guardian to his illegitimate daughter Rupertina.

The Dobson Picture is packed full of symbols of loyalty. It portrays Prince Rupert as the saviour of the Royalist cause. His colours, the pink, the grey and the black, swathe the pillar of strength in the back of the picture. The same colours are on the cockade that is being dipped into the red wine, which will be raised in loyal toast to the King. The crossed gloves symbolise politics and the monarchy. The picture also contains the ultimate symbol of loyalty – a dog with Prince Rupert’s initials monogrammed onto its collar. It is gazing up at Rupert with devotion.

Rupert was renowned for his love of animals, a curious and rather endearing trait in a man also known for his ferocity in battle. In this he was said to take after his mother who preferred “her dogs, her hunting and her monkeys” to her children, apparently in that order. Her preference for her pets may explain why Elizabeth of Bohemia was estranged from all of her children at one time or another.

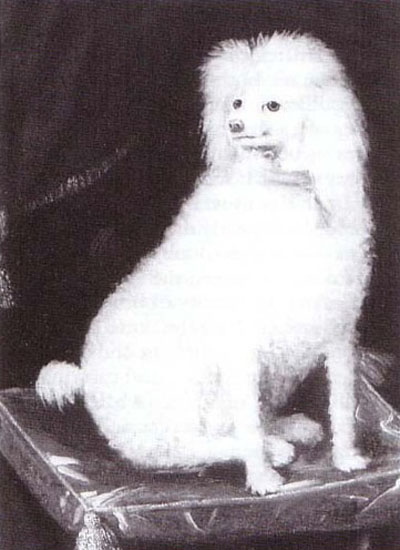

Prince Rupert’s most famous dog was a Standard Poodle called Boy who ran with his cavalry. Boy was a particular target for the Roundheads, who became obsessed with the idea that he was Rupert’s familiar and attributed to him various magic powers, including that he was fluent in various languages, that he was invulnerable in battle and that he could put a spell on the enemy. Boy began to feature in Roundhead propaganda. A pamphlet of 1643 “Observations upon Prince Rupert’s Dogge called Boy” reported that Boy sat beside Rupert in meetings of the King’s Council and that Charles I allowed him to sit on the throne. Boy attended church services and was the toast of the Royalists after various victories. The Roundheads tried both poison and prayer to destroy “this Popish, profane dog, more than halfe a divill, a kind of spirit.” Although the dog was a white poodle they portrayed him as black in the pictures in order to associate him more closely with the devil.

Perhaps inevitably, Boy fell prey to a Roundhead bullet at the Battle of Marston Moor and proved not to be invulnerable after all. The Puritans claimed in another pamphlet “A Dog’s Elegy or Rupert’s Tears” that Boy had been killed by a valiant soldier who had skill in necromancy. The verse ran: “Lament poor cavaliers, cry, howl and yelp, For the great losse of your malignant whelp.” Poor Boy! In an age of superstition it is easy to see how men might attribute magic powers to such a creature and also why the enemy might use Boy as a symbol of the Royalist cause. In the same way it is easy to see how Boy was a talisman and mascot to the Royalists who mourned his loss very deeply. He went down in the army records as the first official British Army Dog, which seems a fitting tribute to a loyal pet.

With thanks to Nicola Cornick

An Unknown Officer

oil on canvas, 30.5in x 25.5in

For over one hundred years this mysterious portrait was traditionally said to depict the famously tragic ‘Rye House Plot’ rebel Lord William Russell (1639 – 1683). However, thanks to Chris Gravett, Curator at Woburn Abbey, recent research has thrown this identification into doubt, especially compared with the other contemporary prints, portraits and miniatures in existence.

The current school of thought is that this might indeed be a portrait by the renowned royalist Civil War painter, William Dobson. Dobson’s unmissable style consisting of thick, confident and meaty impasto brushwork is evident in much of the lower half of the painting. Particularly confident areas are the drapery in the sash and yellow frilled edging, which is executed with a quick and painterly touch. The face also shows some promise, especially in the eyes and mouth. Despite this, the face does seem to be quite flat compared with the rest of the work more reminiscent of the early works by Sir Peter Lely.

The current condition of the portrait is probably the greatest source of uncertainty regarding the attribution. Many of the portraits in this room were cut down during the eighteenth century to fit into the ‘kit-cat’ style panels and were relined and treated heavily with linseed oil during the 1950’s. Thick discoloured varnish currently makes the brushwork and depth of the face incredibly difficult to read. Another feature currently lost in the composition is the remains of what seems to be a column on a seemingly cracked or broken base in the background on the right. No doubt if the painting was cleaned an attribution to Dobson could indeed be more plausible.

Many of the great collection of seventeenth century portraits at Warwick Castle were collected by collector and connoisseur George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick. He amassed in his own words “a matchless collection of pictures by Van Dyck and Rubens” which eventually led to his humiliating bankruptcy in the early 19th century. However, after the sale of many of the castle’s greatest treasures in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the collection has suffered from general neglect from the academic world as a whole, hence why many pieces are still shrouded in mystery!

by Adam Busiakiewicz

An Old and a Younger Man > John Taylor and Sir John Denham

An Old and a Younger Man actually depicts two fascinating poets in the court of Charles I, John Taylor (1578-1653) and Sir John Denham (1615-1669).

Taylor, on the left, was the self-styled ‘Water Poet’, a prolific supporter of the King whose nickname originated from his first profession as a Thames waterman. Following the outbreak of Civil War, Taylor left London in 1643 and followed Charles I and his court to Oxford. Charles I entrusted Taylor with the job of Royalist Water Bailiff, a position of great importance. His job was to keep the complex waterways of Oxford clean for use and to preserve public health, as well as to ferry ammunition, food and fuel for soldiers.

On the right, Denham was a cavalier poet, whose most famous work, Cooper’s Hill, was an accomplished piece of Royalist propaganda. Using a description of the Thames as the entry point for a series of historical and philosophical ruminations upon the state of the nation, Cooper’s Hill can be counted among the most influential poems of its time.

We have images of these characters that bear strong resemblances to the men painted by Dobson. A portrait of a younger Taylor still hangs in the Watermen’s Hall, inscribed ‘J. Taylor the Water poet’, displaying his characteristic goatee beard and moustache. As for Denham, a painting from 1661 inscribed ‘S. John Denham’ depicts a man with the same flowing ringlets and moustache as in Dobson’s painting.

Supporting these biographical and visual identifications is Dobson’s use of iconography. The bust of Apollo covered by Denham’s left hand is a symbol that re-appears in several Dobson paintings to associate the sitter with the Arts, particularly poetry. But the chief element is the fountain on the right featuring a cupid riding a dolphin. This alludes to Taylor’s profession as a waterman, for dolphins have been associated with the Watermen’s Hall since its inception in 1555, and its crest depicts two dolphins either side of a boat.

The motif of cupid riding a dolphin is also a common Baroque allegory that traditionally represents the power of love over all beings. It may refer to the death of Taylor’s wife in 1643, which would explain both the tear in Taylor’s eye and the gesture of comfort offered by Denham. But it is more likely that the ‘Love Conquers All’ motif alludes to the relationship of the two poets to their King. The picture can be understood as a display of loyalty to their monarch from two ardent Royalist watermen, pledging their allegiance in troubled times.

The theme of water is continued in the portrait’s background landscape. The scene shows the banks of the River Thames, the place of Taylor’s work and the subject of Denham’s Cooper’s Hill. Also featured in the background are a castle and a cottage. The castle may be a representation of Farnham Castle, where Denham was governor at the outbreak of the Civil War. The contrasting cottage, meanwhile, may be taken to refer to Taylor’s more humble origins, and may even be an image of The King’s Head in Abingdon, an alehouse owned by Taylor’s brother.

An Unknown Musician > William Lawes

For a while it was thought that this painting might represent Henry Lawes, Gentleman of the Chapel Royal and a composer in the court of Charles I. But comparison with a painting of Henry, possibly by the artist Lely, has placed this identification in doubt. However, we believe Dobson has actually captured Henry’s brother, William Lawes, a lute player and composer who was a particular favourite of the King during the Civil War.

William Lawes spent nearly all his adult life in the King’s employ, composing secular music and songs for court masques, as well as sacred anthems and motets for Charles’ private worship. Charles I was a great patron of the arts and loved music as much as painting. At the outbreak of Civil War, Lawes joined the Royalist army and was given a post in the King’s Life Guards, which was intended to keep him out of danger. However, he was killed by a Parliamentarian in the rout of the Royalists at Rowton Heath, near Chester, on 24 September 1645.

The King instituted a special mourning for William, apparently honouring him with the title ‘Father of Musick’. The background of Dobson’s painting features a singing goddess, and what appear to be the remains of a shadowy loot player. The rose on the left must refer to Lawes’ most famous lyric – “gather ye rose buds”. The bust the musician rests his hand on is a representation of the King. A loyal musician is swearing allegiance to a musical monarch.

An Unknown Officer > William Cavendish (?)

This painting at Knole House may represent William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle. Cavendish was a fascinating character and a man of many talents. He was a polymath, aristocrat, poet, equestrian, playwright, swordsman, politician, architect, diplomat and soldier. He was also a courtier of James I, and later became good friends with Charles I and his wife Henrietta Maria, for whom he hosted lavish banquets. A fierce Royalist, he was made a general during the Civil War.

The symbolism in An Unknown Officer is not particularly obvious, but the column wrapped with vine may be a visual representation of “Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue”, a concept linked to Cavendish through the decoration of his retreat Bolsover Castle, and the title of a masque, written by Ben Jonson and performed in the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace to James I, featuring the young Prince Charles. It is a play on a Herculanean myth where the hero is forced to choose between Pleasure or Virtue, a theme Dobson used in his self-portrait at Alnwick Castle.

In this reading of An Unknown Officer, the vine represents Bacchanalian wine and by extension Pleasure, whilst the column is steadfastness or Virtue. They are intertwined so as to be reconciled, reflecting lines from Jonson’s masque:

Come on, come on! and where you go,

So interweave the curious knot

As ev’n th’ observer scarce may know

Which lines are Pleasure’s and which not.

Visually, the sitter bears a strong resemblance to a painting of Cavendish by Van Dyck. But typical for Dobson, the artist has added quite a few pounds in weight to his sitter, and this is the case for most of his Civil War portraits. He presents strong, robust characters in the presence of turmoil.

However, one clear problem is Dobson’s depiction of the eyes. There is a notable difference between Van Dyck’s depiction of the man’s face and Dobson’s. The details are minor, but Van Dyck shows Cavendish as having ‘covered’ eyelids, whilst Dobson presents a man with ‘hooded’ and prominent eyelids. For this reason, we cannot be certain that An Unknown Officer represents William Cavendish.

What next?

There are still more Dobson paintings to be identified. If you fancy some art historical detective work, why not try investigating the sitters in these paintings?

An Unknown Man at Corsham Court

An Unknown Naval Commander at the National Maritime Museum

An Unknown Officer at the Victoria and Albert Museum

An Unknown Woman at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery